Giant pericardial mass case report: role of echocardiography

Introduction

Cardiac masses are uncommon and they can be classified as tumors or non-tumoral masses that include thrombus and cysts. Primary cardiac tumors are rare, with a prevalence of approximately 0.02–0.056% (1,2). Tumors are distinguished in benign tumors, tumors of uncertain biologic behavior, germ cell tumors, and malignant (3). Primary pericardial neoplasms are very rare and they are detected incidentally during routine cardiac imaging in asymptomatic patients (4); their prevalence ranges from about 0.001% to 0.007% (5). Some cardiac masses can present with systemic symptoms or symptoms related to their localization.

Imaging plays a central role in the diagnosis of cardiac masses; chest X-ray is often the first step and it usually shows enlarged cardiac silhouette with abnormal mediastinic contour (6). Echocardiography is always performed because it is a non-invasive and economic tool; it can reveal the cardiac mass and from its characteristics, it may indicate benign or malignant aspect and so it may help in the differential diagnosis, together with cardiac computed tomography (CT) scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). We report the case of a patient with a giant pericardial mass. We present the following case in accordance with the CARE reporting checklist (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/acr-20-141).

Case presentation

An 82-year-old man was admitted to the hospital for great dyspnea and lower-extremity edema, started some days previously. He was a former smoker and he had history of hypertension and high uric acid level. He took antihypertensive drugs.

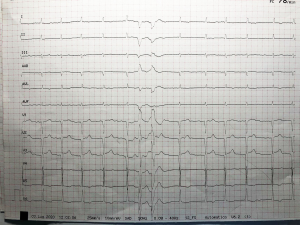

On hospital admission his blood pressure was 100/60 mmHg, heart rate 80 beats per minute, 22 breaths per minute and temperature 36 °C. Electrocardiogram performed in the Emergency Department showed atrial fibrillation at medium rate and two ectopic ventricular beats (Figure 1); blood tests showed low levels of cardiac enzymes (high-sensitivity troponin T 25 ng/L, myoglobin 50 ng/mL, creatin kinase-MB 0.8 ng/mL), and high levels of NT-pro-BNP (3,000 ng/mL); patient’s serum creatinine level was 1.31 mg/dL corresponding to calculated eGFR 34 mL/min, azotaemia levels were 110 mg/dL, hemoglobin 14 g/dL, platelet count 200,000/mm3, protein C reactive 10.6 mg/dL,acid uric level 14.9 mg/dL. Patient executed chest X-ray that indicated a great increase in heart silhouette and pleural effusion (Figure 2).

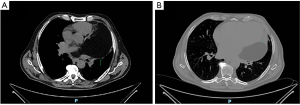

Chest-CT with contrast agent demonstrated mild increased interstitial markings and a large, low-attenuation intrapericardial lesion with no enhancing components (Figure 3). It also revealed pleural and pericardial effusion.

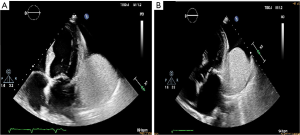

The echocardiography performed on the admission day showed a great pericardial mass measuring 4 cm × 10 cm that appeared to arise from the left atrioventricular groove and was adjacent to the anterior, posterior and lateral walls of the left ventricle and to the left atrium (Video 1). It did not invade into the epicardial fat or myocardium; it was iso/hypoechoic, well circumscribed, non-contractile, homogeneous and with a clear separation from the wall, probably encapsulated (Figure 4).

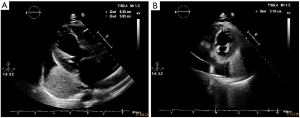

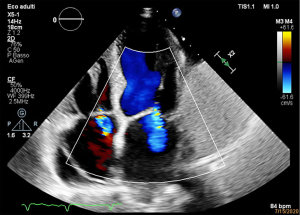

There was even a great pericardial effusion but there were no signs of cardiac tamponade (Figure 5). Transthoracic echocardiogram showed dilated left ventricle with global hypokinesia and a severe reduced ejection fraction of 28%; main pulmonary artery was dilated and there were sever functional mitral regurgitation and moderate tricuspid regurgitation (Figure 6). During the hospitalization a coronary angiography was performed, detecting no coronary arteries stenosis.

Administration of intravenous diuretics was started and Cardiac-MRI was purposed, but in one week patient’s clinical condition improved and he was discharged from the hospital. He refused additional exams.

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Discussion

The most common benign pericardial tumor is lipoma but the most common pericardial mass is a cyst. Mesothelioma is the most common primary malignant pericardial tumor (7).

Patients with primary pericardial neoplasms can present with symptoms that include exertional dyspnea, chest pain, cough, palpitations, fatigue, night sweats, fever, and facial or lower-extremity edema (5).

The echocardiography can identify the mass, its localization, extension, size and even tissue characteristics. Echocardiography has a narrower field of view than MRI or CT in general (4), but it plays a central role in the first approach to the patient with cardiac symptoms because it can be performed in the Emergency Department, it is an economic, simple, non-invasive test. It may aid to diagnosis, prognosis, treatment and patient follow-up of cardiac masses. In this case, echo characteristics suggested that the mass was a lipoma that is composed by adipose tissue.

Lipomas are primary benign cardiac tumors that frequently develop from the subendocardium, but they may also grow from the pericardium or on the cardiac valves (4).

On echo lipoma tends to be homogenous without evidence of calcification, hyperechoic in the cavity and hypoechoic in the pericardium. It usually is broad based, immobile, without a pedicle and well circumscribed, sometimes with a capsule (4); pericardial lipoma tends to be less capsulated (5).

Small lipomas are often asymptomatic and found incidentally, whereas great or pericardial lipomas may manifest with symptoms such as compression of coronary arteries, arrhythmias, and outflow obstruction (8,9). They can become giant without producing any symptoms because their growth is slow. A case of giant pericardial lipoma that induced cardiac tamponade was described on August 2019 (10). We reported a case of giant pericardial lipoma that probably produced pericardial effusion but this may have been induced also by the heart failure. Thereby heart failure may derive by mass compression of cardiac chambers. We can also assume it because the coronary angiography performed during the hospitalization did not show any atherosclerotic plaque. Moreover, mitral regurgitation stems from the severe left ventricle dilation and the consequential leaflet tethering.

Thanks to a detailed anamnesis, we found that pericardial mass was identified twenty years ago on a chest-CT. Because of mass favorable echocardiographic characteristics, size and time of the development, we purposed that it was a lipoma.

Surgical resection is necessary to prevent tumor compression syndromes of the heart and even to exclude a malignant process by histological examination of excised specimens (11). In fact, even if it is very rare, great mass may evolve in liposarcoma.

In this case we remarked the central role of echocardiography as technique of choice to first approach in patient with cardiac mass and we recommended the choice of surgical resection even if the tumor is benign and asymptomatic.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the CARE reporting checklist. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/acr-20-141

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/acr-20-141). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Lam KY, Dickens P, Chan AC. Tumors of the heart. A 20-year experience with a review of 12,485 consecutive autopsies. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1993;117:1027-31. [PubMed]

- Reynen K. Frequency of primary tumors of the heart. Am J Cardiol 1996;77:107. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Travis WD, Brambilla E, Burke AP, et al. WHO Classification of Tumors of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus and Heart. 4th ed. International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, France; 2015.

- Mankad R, Herrmann J. Cardiac tumors: echo assessment. Echo Res Pract 2016;3:R65-R77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Restrepo CS, Vargas D, Ocazionez D, et al. Primary pericardial tumors. Radiographics 2013;33:1613-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grebenc ML, Rosado de Christenson ML, Burke AP, et al. Primary cardiac and pericardial neoplasms: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics 2000;20:1073-103; quiz 1110-1, 1112.

- Patel J, Sheppard MN. Pathological study of primary cardiac and pericardial tumours in a specialist UK Centre: surgical and autopsy series. Cardiovasc Pathol 2010;19:343-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Araoz PA, Mulvagh SL, Tazelaar HD, et al. CT and MR imaging of benign primary cardiac neoplasms with echocardiographic correlation. Radiographics 2000;20:1303-19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Barbuto L, Ponsiglione A, Del Vecchio W. Humongous right atrial lipoma: a correlative CT and MR case report. Quant Imaging Med Surg 2015;5:774-7. [PubMed]

- Kerndt CC, Balinski AM, Papukhyan HV. Giant Pericardial Lipoma Inducing Cardiac Tamponade and New Onset Atrial Flutter. Case Rep Cardiol 2020;2020:6937126 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Steger CM. Intrapericardial giant lipoma displacing the heart. ISRN Cardiol 2011;2011:243637 [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Russo D, Cinque A, Velardi L, Schino S, Perrone FNS, Beggio E, Romeo F, Gaspardone A. Giant pericardial mass case report: role of echocardiography. AME Case Rep 2021;5:23.