Case report: presentation of delayed tracheal perforation after hemithyroidectomy

Introduction

Hemithyroidectomy is a safe procedure performed for benign as well as some small, differentiated thyroid malignancies. The complication rate of hemithyroidectomy is lower than that of total thyroidectomy, and include hypocalcemia (7.1%), hematoma (1.2%), respiratory complications (0.8%), vocal cord paralysis (0.6%), and bleeding (0.2%) (1). Tracheal injury during total thyroidectomy is rare. A 2005 review of 11,917 thyroidectomies reported two cases of tracheal perforation identified intraoperatively during partial thyroidectomy (0.02%). A small body of literature identifies trends in cases of tracheal injury in thyroidectomy: most injuries are noted intraoperatively, occur posterolaterally in the relatively less vascular region of the ligament of Berry, and generally follow suture ligation of vessels or use of diathermy to dissect the thyroid off of the trachea. Intraoperative injuries are generally repaired primarily at the time of injury with little morbidity (2).

Case report

A 25-year-old man presented with a 4-centimeter right thyroid nodule. Fine needle aspiration was consistent with atypia of undetermined significance and molecular testing positive for NRAS oncogene mutation. The left thyroid lobe was unremarkable on ultrasound. An uncomplicated right thyroid lobectomy and isthmusectomy were performed under general endotracheal anesthesia, with a size 6 mm neural integrity monitor (NIM) electromyogram endotracheal tube for recurrent laryngeal nerve monitoring. Prior to closure, a Valsalva maneuver was performed without subsequent air escape, and no intraoperative tracheal injury was identified to visual inspection. Estimated blood loss was minimal. The patient was discharged on the day of surgery with post-operative instructions including abstaining from lifting over 10 pounds for 2 weeks. Pathology reported a 30-gram thyroid lobe with a 4-centimeter papillary carcinoma, classical variant, as well as an 8-millimeter papillary thyroid microcarcinoma.

The patient was seen in clinic on post-operative day 21 for routine follow-up. At that time, examination revealed the patient’s incision was healing well and there was no crepitus or peri-incisional swelling. The patient did not complain of changes to the appearance of the incision upon Valsalva, and voice, swallow and breathing were normal. The patient reported compliance with the activity restrictions, and was advised to gradually return to activity as tolerated.

On post-operative day 27, the patient reported a golf-ball sized “lump” inferior to his incision that appeared immediately after a set of pull-ups. He was otherwise asymptomatic. The patient observed that the collection diminished in size over time but re-accumulated to its original size each time he bore down (Figure 1). He was evaluated at an outside hospital emergency department, where he was determined to be stable and discharged.

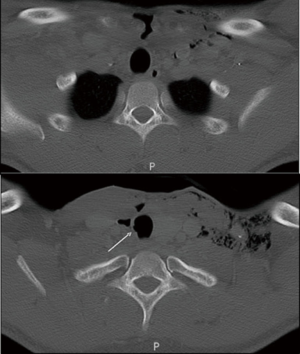

He was seen in clinic on post-operative day 29, where needle aspiration of the 4-centimeter by 4-centimeter ballotable pocket did not yield air or fluid. A pressure dressing was placed on the patient’s anterior neck with instructions to apply manual pressure to the area with cough or strain, and he was admitted to the hospital. A computed tomography of the neck with intravenous contrast was obtained revealing extensive subcutaneous air tracking to the surgical bed, with irregularity of the right lateral trachea at the level of the first and second tracheal ring (Figure 2).

A bedside laryngobronchoscopy after trans-tracheal delivery of 4% lidocaine topical anesthetic was performed which identified a 1-millimeter mucosal irregularity along the lateral right tracheal wall inferior to the cricoid, with overlying scant granulation tissue. Bedside neck exploration was then performed for evacuation of the air pocket, with successful air egress. A Penrose drain was placed beneath the strap muscles at the level of the tracheal injury. The skin site was closed around the drain, and an overlying pressure dressing applied. The patient’s crepitus resolved by the following hospital day, and he was discharged to home with activity instructions limited to “minimal” for 4 weeks. The patient was seen in clinic four days after discharge for drain removal and drain site closure. During 1 year of follow-up, he had no recurrence of crepitus or subcutaneous air.

Discussion

Delayed tracheal perforation has previously only been reported after total thyroidectomy. We have identified seven previous cases of delayed tracheal perforation after total thyroidectomies without neck dissection, all presenting with subcutaneous emphysema (3-9). The range of post-operative day of presentation is 4–21 days, with a median of 8 days. Two of these cases were managed conservatively with success (4,6). One repair required circumferential tracheal resection and primary anastomosis to repair anterior tracheal necrosis involving multiple tracheal rings (7). The remainder of delayed perforations described were closed with absorbable suture, some including rotational muscle flaps. Rotational muscle flaps were utilized to repair larger lacerations (8,9) and one rupture complicated by infection (3).

Previous reports have attributed delayed injury in total thyroidectomy to bilateral devascularization of the trachea resulting in ischemia and necrosis. The trachea is supplied by lateral pedicles drawing vessels from the inferior thyroid, subclavian, supreme intercostal, internal thoracic, innominate, and superior and middle bronchial arteries. These longitudinal pedicles arborize with the contralateral vascular supply through transverse vessels that course in the soft tissue between the cartilages (10). In partial thyroidectomy, this bilateral blood supply likely protects the trachea from devascularization, putting the trachea at higher risk for injury during total thyroidectomy, where the field of dissection potentially violates collateral vasculature.

The case presented here is the first reported delayed tracheal injury following partial thyroidectomy. In the opinion of the surgeons, the injury as visualized on bedside tracheobronchoscopy appeared to be coagulative necrosis secondary to thermal energy transmitted by bipolar cautery. The tracheal mucosal lesion was located in the less vascular region of the ligament of Berry. It is possible that the transverse vessels were cauterized, or the area of injury was a watershed. In our case, devascularization with or without direct thermal injury most likely weakened an area in the fibrocartilaginous tracheal wall, making it susceptible to rupture during episodes of increased intrathoracic pressure.

An additional potential contributing factor in this case was the etiology of the thyroid disease. The NRAS mutation detected as part of a next-generation gene sequencing panel is known to confer a 60–80% chance of cancer risk or cancer potential, most frequently follicular variant of papillary carcinoma (11-13). Total lobe resection is more important in an operation to extirpate a presumed malignancy. In addition, the patient underwent isthmusectomy, necessitating more extensive dissection. Finally, the patient was a young, healthy male who returned to an intensive workout regimen after the 2-week activity restriction period, leading to the acute elevations of intrathoracic pressure that unmasked the weakness in the tracheal wall.

Strict activity restrictions are of paramount importance in the post-operative period. Restrictions at our institution include lifting no more than 10 pounds, abstaining from strenuous activity, and returning to the preoperative level of activity slowly by adding activities of daily living back incrementally over the course of 2 weeks. Delayed injury from coughing and sneezing are reported in the total thyroidectomy literature; here, the intrathoracic pressure was generated during pull-ups. Our tracheal perforation occurred 27 days post-operatively. Given the rarity of this event and the median post-operative day of subcutaneous emphysema in total thyroidectomy cases of 8, we have not changed our post-operative activity restrictions. However, the slow return to preoperative levels of activity will be emphasized for future patients.

Management of delayed tracheal perforation depends largely on the stability of the patient presenting with subcutaneous emphysema after thyroid surgery. Large pneumothorax, cardiorespiratory distress, enlarging subcutaneous air, and tracheal deviation are among indications for emergent airway management and surgical exploration. In the patient with a stable air pocket without acute distress, however, conservative management is a reasonable option without the added morbidity of emergent interventions and general anesthesia. Two previous reported cases cite conservative management of pretracheal distension and imaging-confirmed subcutaneous air (4,6). In the case presented herein, the authors elected to open the incision bedside, insert a Penrose drain to achieve air egress and place a compressive dressing with one inpatient night of monitoring. Our patient did not experience reaccumulation of air after drain and dressing removal, suggesting that conservative therapy is appropriate in select patients.

Surgeons who perform thyroidectomies should be aware of the possibility of delayed tracheal perforation even one month post-operatively. Contributing factors include use of diathermy, and episodes of increased intrathoracic pressure. Care should be taken when using diathermy to dissect the thyroid off the trachea, especially in the less vascular region of the ligament of Berry. Activity restrictions, slow return to activity, and monitoring for postoperative peri-incisional swelling with a high index of suspicion for tracheal violation are paramount. Conservative therapy may be appropriate for the stable patient.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this manuscript and any accompanying images.

References

- Hauch A, Al-Qurayshi Z, Randolph G, et al. Total thyroidectomy is associated with increased risk of complications for low- and high-volume surgeons. Ann Surg Oncol 2014;21:3844-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gosnell JE, Campbell P, Sidhu S, et al. Inadvertent tracheal perforation during thyroidectomy. Br J Surg 2006;93:55-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bertolaccini L, Lauro C, Priotto R, et al. It sometimes happens: late tracheal rupture after total thyroidectomy. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2012;14:500-1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Conzo G, Fiorelli A, Palazzo A, et al. An unpredicted case of tracheal necrosis following thyroidectomy. Ann Ital Chir 2012;83:55-8. [PubMed]

- Damrose EJ, Damrose JF. Delayed tracheal rupture following thyroidectomy. Auris Nasus Larynx 2009;36:113-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Davies P, Alhamarneh O, Campbell JB. Conservative Treatment of Delayed Tracheal Perforation Following Thyroidectomy. The Otorhinolaryngologist 2013;6:119-21.

- Jacqmin S, Lentschener C, Demirev M, et al. Postoperative necrosis of the anterior part of the cervical trachea following thyroidectomy. J Anesth 2005;19:347-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mazeh H, Suwanabol PA, Schneider DF, et al. Late manifestation of tracheal rupture after thyroidectomy: case report and literature review. Endocr Pract 2012;18:e73-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sanna S, Monteverde M, Taurchini M, et al. It could suddenly happen: delayed rupture of the trachea after total thyroidectomy. A case report. G Chir 2014;35:65-8. [PubMed]

- Salassa JR, Pearson BW, Payne WS. Gross and microscopical blood supply of the trachea. Ann Thorac Surg 1977;24:100-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nikiforov YE, Carty SE, Chiosea SI, et al. Highly accurate diagnosis of cancer in thyroid nodules with follicular neoplasm/suspicious for a follicular neoplasm cytology by ThyroSeq v2 next-generation sequencing assay. Cancer 2014;120:3627-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nikiforov YE, Carty SE, Chiosea SI, et al. Impact of the Multi-Gene ThyroSeq Next-Generation Sequencing Assay on Cancer Diagnosis in Thyroid Nodules with Atypia of Undetermined Significance/Follicular Lesion of Undetermined Significance Cytology. Thyroid 2015;25:1217-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nishino M, Nikiforova M. Update on Molecular Testing for Cytologically Indeterminate Thyroid Nodules. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2018;142:446-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Windon MJ, Dhillon V, Tufano RP. Case report: presentation of delayed tracheal perforation after hemithyroidectomy. AME Case Rep 2018;2:24.